A Quick Start on Simple Estate Planning: Your will

Your last will and testament is probably what you thought of first when you thought of estate planning. It contains your directions for who gets your property after you die. But it does some other important things as well:

- It names a personal representative (other states call this person an executor).

- If you have minor children, it can nominate guardians for them.

- It determines who gets your tangible personal property (the stuff around the house).

- It makes any specific gifts you want to make, such as leaving $5,000 to a charitable organization.

- It distributes your remaining property. This is everything you own that wasn’t distributed as tangible personal property or a specific gift.

- Finally, it can create a trust after your death to:

- Hold distributions for your young children until they reach a responsible age; or

- Hold distributions to incompetent or disabled beneficiaries (of any age) in a way that allows someone else to manage the assets and doesn’t endanger eligibility for government benefits.

Decision: Personal representative

This is the person who will do all the administrative and legal work required to carry out the directions in your will. This person will be in charge of your estate until your final expenses are paid and your final affairs are finished.

A good personal representative is:

- Trustworthy

- Responsible

- Organized

- Reliable

- Good at making decisions

- Good at following directions

- Good at following through and getting things done

- A peacemaker who prevents conflict

- Steadfast if conflict is unavoidable

Few personal representatives have all these qualities. Make the best choice from among the people you trust.

A few more things you should know about your personal representative:

- This person will most likely hire a lawyer to help with the final affairs. Your personal representative doesn’t have to be a legal or financial expert.

- This person can always resign. Nominating them does not force them to do the job.

- The job will probably be easier for someone who lives nearby, or at least in the same state.

- You can have more than one personal representative at the same time. Two or more people can share the job as co-personal representatives.

You should also name at least one successor personal representative. You never know if the primary person will be available, so you need a backup.

If you are married, it’s common to name your spouse as your primary personal representative. A trusted adult child or sibling also often serves as personal representative. But you can name any adult you trust, no matter their relationship to you.

Consider:

Who might be a good primary personal representative for you?

Who might be a good backup?

Decision: Tangible personal property

Your tangible personal property is what I like to call “the stuff around the house.” This includes movable personal property like jewelry, heirlooms, paintings, tools, sports equipment, electronics, furniture, cars, and hobby collections.

For the few sentimental items and heirlooms you want to go to specific people, your will incorporates a memorandum of personal property. This is a list of specific items and who will receive them, signed and dated by you after you execute your will. For now, focus on deciding what should happen to the rest of your stuff.

If you are married, you should leave most or all of your tangible personal property to your spouse first. If you are not married or if your spouse dies before you, this property is commonly left to the children in equal shares, with the provision that they can work out how to divide everything among themselves.

Consider:

Who do you want to receive your tangible personal property?

Your spouse?

Your children? In equal shares?

Someone else?

Decision: Specific gifts

Specific gifts are usually small gifts of money or specific assets that happen before the big distribution of everything else. For example, “I give $5,000 to my church” and “I give my cabin up north to my daughter Emily” are specific gifts.

Remember, these gifts happen before the general “I leave everything to my spouse and children” kind of distribution. So if you only had $5,000 left in your estate after paying expenses, taxes, and debts, the church would get everything and your spouse and kids would get nothing. That’s an unusual situation, but something to keep in mind.

Most of my clients do not make specific gifts in their wills. They prefer to make these kinds of gifts during their lifetimes and let everything at death go to their spouse or children. But it is certainly an option, especially if you feel strongly about making a charitable donation at your death or want to ensure a particular asset goes to a particular person.

Consider:

Do you want to make any specific gifts?

Decision: Remaining property

Called the remainder in legal parlance, this is the big distribution of “everything else” in your estate after expenses, taxes, debts, and specific gifts. This is what most people think of when they think of making a will.

My clients usually want to leave all their remaining property to their spouse first (if they have one), and then to their children equally (and, if a child happens to die before them, to grandchildren, etc.). Sometimes clients want to disinherit a child or, if childless, distribute their property to someone other than close family.

Consider:

Who do you want to receive your property first?

Your spouse?

Your children? In equal shares?

Someone else?

Who do you want to receive your property second, if your primary beneficiary has died?

Your children? In equal shares?

Someone else?

Decision: Guardians for young children

If you have young children, this is the most important reason to make a will. Who do you want to take care of them if you can’t? You’ve probably put a lot of thought into this already. For some this is an easy decision; for others it is the most difficult.

Here are a few things to consider in making this very personal decision:

- Close family—those most involved in your children’s lives—usually make the best guardians.

- If you are married, you and your spouse should nominate the same people. If you don’t nominate anyone or nominate different people, you might be setting your two families up for a fight.

- Make a list of what is most important to you in raising your children. Consider religion, parenting philosophy, values, relationships, location, and lifestyle.

- Consider the resources of the people you might nominate. Keep in mind that your own resources and life insurance will be available to provide for your children, too.

- Think about whether you want your children to be raised by a couple, or if you’re okay with a single person caring for them. What do you want to happen if the couple gets divorced, or if one of them dies? What do you want to happen if that single person gets married?

Wisconsin has two types of guardianships: a guardianship of the person and a guardianship of the estate. The guardian of the person will have custody of your children and fill the parental role. The guardian of the estate will hold and manage your child’s property (what he or she inherits from you, potentially) until your child turns 18. For a young child, the guardian of the person and the guardian of the estate are usually the same person. If you want, though, you can nominate different people. I would only recommend this if you feel strongly that one person or couple should have custody of your children but someone else would be better able to manage their inheritance.

If you’re having trouble making this decision, know that you’re not alone.

Consider:

Who would you trust first to have custody of your children?

Who would you trust to manage your children’s inheritances and provide for them financially?

Who might serve as backups?

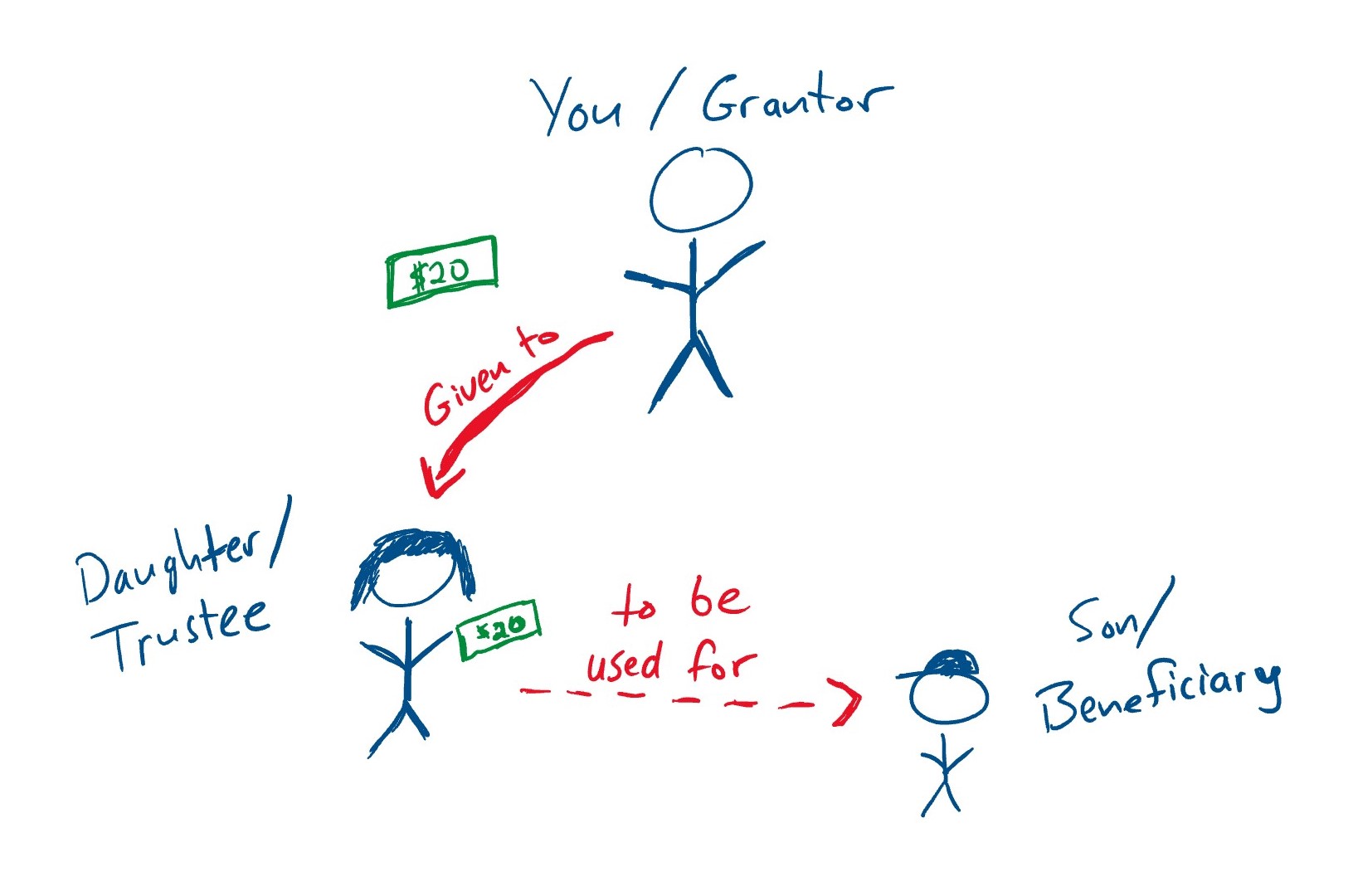

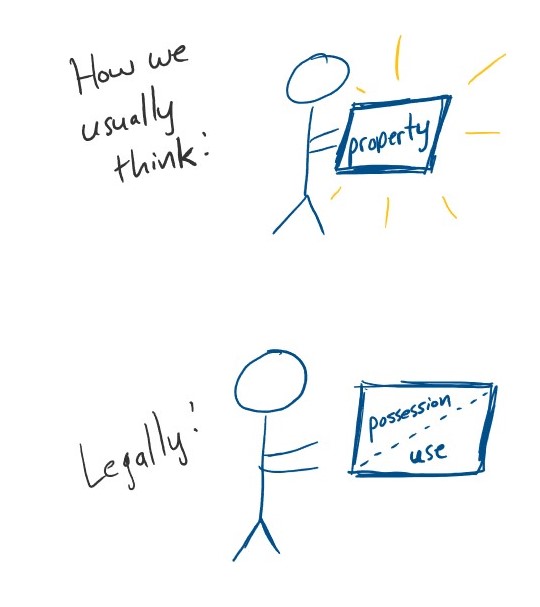

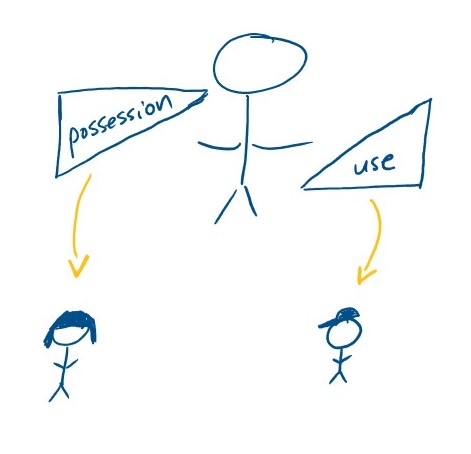

Decision: Trust for young children

If you have a young child, think about what will happen to your property if both you and your spouse die. Even if you nominate a guardian of the estate, whatever you own (including the life insurance benefit) will become your child’s as soon as they turn 18. The way to avoid this is to have your will create a trust to hold the property until an age you choose.

Do you think your child will be able to make responsible and wise decisions with a large amount of money when they are 18? What about when they are 21? When they are 25? When they are 30?

Some of my clients are comfortable giving their child full control of the inheritance at age 18. But if you think it best to have an older, more responsible person control the money until a certain age, you need to have your will create a trust.

If you create such a trust, you also need to decide who that older, more responsible person will be. This person is the trustee. This person is most commonly a family member, and often the same person you’ve nominated as guardian or personal representative. The same qualities that make a good personal representative make a good trustee.

The trustee simply holds the inheritance until your child reaches an age you choose. Most of my clients choose either age 25 or 30 for their child to gain full control of an inheritance. Until then, the trustee invests the property and can spend it for your child’s benefit—it’s just that the trustee makes the final decision to spend or not to spend, rather than your child. You can even direct how you want your trustee to spend the money. For example, you could state that you want the trustee to use the money to pay for your child’s college education.

Consider:

Do you want to create a trust to hold your property for your young children if you die?

At what age are you comfortable with your children receiving full control of their inheritance?

21?

25?

30?

Some other age?

Who should be the trustee managing this property for your children?

The person who is also your personal representative?

The person who is also the children’s guardian?

Someone else?

Who should be the trustee if the person above can’t do it?

The person who is also your personal representative?

The person who is also the children’s guardian?

Someone else?

Next: Your power of attorney for finances (coming soon) >